Archive: November, 2024

Burnout repetere

posted by Jeff | Wednesday, November 27, 2024, 2:33 PM | comments: 0I was going to write about feeling burnout as we enter the holiday season, but it looks like I already did this fall, and do most years.

Not sure why I can't prevent it.

As a bartending enthusiast

posted by Jeff | Tuesday, November 26, 2024, 4:00 PM | comments: 0I think I realized at some point this year that I'm more of a bartending enthusiast than I am cocktail enthusiast. Don't get me wrong, I enjoy drinking a good drink, but I think I like the making of beverages more. This is especially true as I find myself moderating compared to, say, the pandemic days. We hosted a baby shower for a friend in February, and then had a Big Summer Blowout, and in both cases I really enjoyed making drinks for people. I even made a little progress as far as garnishes go.

Renovating the home bar last year I think was a turning point. Prior to that, we had a few bottles of things to make our favorites that we learned on cruise ships, but as I developed a drink menu, I wanted to have more room and make it genuinely functional. With all of those mixology classes on cruises, the spectrum of things that were interesting to me kept getting bigger. The base spirits, mostly rum, vodka, tequila, gin and some kind of whisky, are easy enough, but there are so many liqueurs that make drinks cocktails. I remember one bartender pointing out that you can make almost anything better with St. Germaine, an elderflower infused liqueur, or Chambord, which has a black raspberry flavor. But you also probably need some kind of orange stuff, I use Solerno instead of Cointreau, certain schnapps, Midori, Licor 43, Frangelico, Disaronno, coffee rum, an Irish creme, and of course, we use a lot of flavored rums from Wicked Dolphin. Oh, other add-ons like vermouth, passion fruit stuff, and don't forget Filthy Cherries.

The hard part is that if you want to be able to make all of this stuff when someone randomly visits, you need to stock a lot of backups. Basically everything starts at $25 for a 750ml bottle (rum and schnapps usually less). It gets kind of expensive, and when I look at what we've spent this year, admittedly a lot of it going toward those two big parties, ouch. It's an expensive hobby.

But it's so satisfying to hear people say that they enjoy something you made. It's simpler than cooking or baking, sure, but there really is a sweet spot in how you mix stuff. Too often what you get it too sweet or too boozy. In good bars, it's fine, they want your feedback and they'll remake something if you don't like it. They want that feedback. But most restaurants and lessor places, not so much. It's why I don't get a lot of drinks outside of my home or on cruises. Making drinks for people is more intimate than cooking in a commercial setting, because the person doing the thing is right in front of you.

My next opportunity to serve will be when my Seattle family is in town, and I look forward to that. And to my local friends, the bar is open for you!

My unintentional phone detox

posted by Jeff | Monday, November 25, 2024, 7:30 PM | comments: 0For the past year or so, I've noticed myself using my phone less and less. Sure, I still use it for texting, and all of the NYT games, but I find myself going to it less and less. I can't say that this was intentional, but in the last few months in particular, my usage has sunk.

Keep in mind that I also haven't used notifications for anything other than text, my personal email, and up until recently, news headlines. I've actually never enabled notifications for social media, I don't have work email on my phone, and Slack is restricted to business hours. When the phone is sitting on my desk, it's not asking me to look at it. That obviously goes a long way toward reducing the time wasting.

I've talked about this before, that one of the core issues is that social media stopped being social a long time ago. The algorithm just feeds you a steady stream of pointless shit from advertisers, celebrities and randos that it thinks you will care about. The number of friends posting meaningful things makes for a very terrible signal to noise ratio. If that weren't enough, Facebook can't even get in-app notifications right, so when I post something or respond to them, I never know about it. That also means no dopamine stream from likes. I am using the socials more as a diary. I post photos to Instagram, which forwards to Facebook, and I'll share links of interesting to me things. I'm a writer, not much of a reader.

So when you take out the antisocial media, there isn't a lot left, other than the aforementioned games. I do Wordle, Strands, Connections and the crosswords every day. I use my web-based music app nightly. I read tech news at lunch, aggregated by Feedly. I do utilitarian things like adjust the temperature in the house or turn on lights. It's not that I don't find the device useful, it's that I just don't spend time doomscrolling anymore. It's boring.

I still find myself pulling out my phone in a moment of boredom, but what happens is that I open the 'Gram and scroll a little, see some cats or friend posts, algorithm willing, and a few minutes later I realize how little this is doing for me. I'm starting to realize how much cognitive overhead there is in doing it, and now I choose not to engage too much in it. I think watching others doomscroll, whether it be bored parents at Walt Disney World, or certain older adults in my life, and I think, shit, I don't want that. There are too many thing to be present for, and I say that as a work-from-home person with a fairly small real life social circle.

What I'm starting to see now is that I'm getting a lot of time back, and it moves slower. In some ways it also forces me to think about stuff that is uncomfortable, but that mental bandwidth used to be spent on mindless scrolling. I'll be honest, that's probably not great for my anxiety, but looking at the shit show dumpster fire of online culture was hardly helping my anxiety. There are other things I spend that time on now, including more writing (much of which I never post), reading, mostly technology and science stuff, lots of video games, and all of my usual hobby stuff.

I think I can genuinely say that I feel better, even though the net feels are likely on edge because I have a hard time letting go of injustices and slights that frankly are not easy to change. I spend a lot of time working on that with my therapist. But I'm surprised at how often I get the urge to pull out my phone, and I don't. The other night I was in line to get food at WDW, and it was busy, and I left it in my pocket (missing Diana's text in a different line, oops). It's funny what you observe, if drunken tourists are funny. But even little things like the tile work inside of the Morocco pavilion, or the chefs preparing food, or an overheard conversation about the cider flight at a different stand. There's so much life happening around you, and I promise it's more interesting than anything on a 6-inch screen. Also, WTF if you're at Disney. You can doomscroll at home, where it's cheaper.

If you think I have a judgmental tone about this, you are correct. I owe much of my success to the Internet and the devices that work on it. They're tools that enable a great many valuable things, and I don't want to discount that. But recent research shows that people are spending close to five hours per day looking at their phones, almost a third of their waking time, and of that time, more than a third is on social apps. That ratio is even higher for younger people and active older people. I just can't believe that all of that time spent isn't missing out on something else. The thing that makes it worse is that so many people don't apply critical thinking to what they see online, and I fear that our society is getting dumber, by choice.

So what are my stats? It's hard to get a read on notification counts, because I do have reminders for my work calendar (they're not reliable on the desktop), and I do allow Slack notifications during business hours (they can reach over a hundred some days). My daily unlocks appear to be in the high 30's most days, which is less than expected. Total screen time per day looks to average three hours, and the "winner" most days is NYT Games, accounting for an hour to 90 minutes most days. Feedly is a close second, as my gateway to tech news like ArsTechnica and The Verge, mostly, clocking in at an hour. My Facebook usage varies, and it looks like it counts time reading articles spawned from it, but today it was 12 minutes, and the most I can find is 50. Instagram appears similar, but without the spikes because I'm not reading news from it. Chrome is the next big one, and the sites I spend the most time on are my own.

I feel better using my phone less. Your mileage may vary, but give it a whirl.

The joy of purpose-driven software

posted by Jeff | Friday, November 22, 2024, 10:20 PM | comments: 0I was texting to a former coworker, a guy that reported to me, but not long enough frankly to really get to know him before I, uh, "departed" the company. He asked me if I was still using my home grown music service, MLocker. I told him that, yes, at this point, it has streamed tens of thousands of songs and is used by my entire family. In fact, it's been four years now. As he put it... "The world needs more software like that. Purpose-driven, scratch-your-own-itch type of stuff." I wonder if it could have any potential as a profitable app.

This exchange was extremely flattering, even though he specifically hasn't really taken advantage of my curiosity project. I'm literally listening to music being served by this service right now. While I'm still proud of the longevity of CoasterBuzz and PointBuzz/Guide To The Point, the fact that I use this music app that I built literally every day is uniquely gratifying. I can't think of anything else that I've ever built that is so regularly used by me and my family. Putting aside my preference to own music instead of subscribe to it for a moment, what I made is the functional equivalent of those huge subscription services. And it lands in a profound way because, as I'm sure many can agree, music is an integral and important part of my life.

I've had a great many ideas over the years around "good" ideas for software, and made many of them real. It's a little frustrating though how none of them were likely to become a business. There are two ideas that I've prototyped that theoretically could be this. One is a social media clone that has no algorithm, no ads, just friends posting stuff, but I've mostly left it. People tell me they're interested, but would they give me money for it? I also have a theme park idea that wouldn't net a ton of money, but it's a fun idea. I should flesh that out, even if it's just for the fun of it. Friends know what that is.

The non-mystery around my triglycerides

posted by Jeff | Friday, November 22, 2024, 2:00 PM | comments: 0I had another blood draw yesterday for lipids, and my triglycerides are down 25% from two months ago. The only real change has been more movement (walking), though not yet as regular as it likely should be. They're still high, 276 mg/dL (150 is normal, up to 200 is "borderline"), but trending in the right direction.

This has been weird because it appears that most people who respond well to a statin, and my LDL "bad" cholesterol is "optimal" and below normal according to the lab, also see their TG's go down. Mine, stubbornly, have not, over the last three years, when I started taking rosuvastatin. Even when I was actively exercising, back in 2005, I registered a high 300's once. Admittedly, my diet was not good then. I had just cut beef from my diet, too. But it does seem like my normal has always been stubbornly high. I don't respond well to other drugs meant to treat the high TG's, so exercise is probably all I've got.

I've read a lot of medical journal papers on this subject, and it's interesting stuff. The 150 designation as normal is essentially the mean value across the majority of people, which feels kind of arbitrary. The problem is that LDL and triglycerides, typically, are high together, and LDL is known to be a risk factor for cardiac events. It's not clear that high TG's do the same. One study, a few years old, concluded that high TG risk for cardiac events levels off at 150. They are known to cause some hardening of arteries, and extremely high can cause pancreatitis (my related labs for that are all good). So it's not that I don't take it seriously, I'm just not convinced that science can show conclusively that the high-ish levels I tend to have are any worse than being at 150.

Anyway, the point is I need to get off my ass more. That problem is entirely psychological, and I talk to my therapist about that one.

America has a science problem

posted by Jeff | Thursday, November 21, 2024, 5:00 PM | comments: 0Growing up in the inner-city Cleveland school district, in the midst of desegregation (or "bussing," as white adults liked to call it), I vividly remember lessons about the importance of math and science. It was a point of patriotism that we, Americans, had been on the forefront of technology, even in the 70's as many industries began to change. We'd go to our local NASA museum, see the moon rock, or the health museum to see how medicine was allowing us to live longer. (I also remember a computer that estimated your longevity, my first real chance to contemplate death, at age 8.) I found it to be inspiring and exciting. And while I didn't understand geopolitical and economic issues at the time, it seemed like a good thing that we were "better" at this stuff than the Soviets. For those who don't remember, the Soviet Union was the communist government that included Russia and surrounding countries. Ugh, that I feel like I need to qualify that plays into my eventual point.

These days, the US is not leading so much. According to a list of PISA/OECD rankings on Wikipedia, from 2022, we rank 34th in math, 16th in science and 9th in reading education. There are only 193 countries in the world. Yikes. Because of COVID, they don't have China listed, but they were 6th in math an 10th in science in 2015. Most of Asia and Europe outrank us, and Singapore is #1 in all three categories. Why does this matter? Because much of American economic identity is rooted in being first at things, most at things, inventing things. We have to educate leaders and the general population to have those achievements. I don't think economic nationalism makes sense, because you can't reverse globalism, but to be "winning," you can't be behind your next biggest economies like China.

This isn't a problem with teachers, I don't think. They're overworked, underpaid, and most of those that I get to know are aspirationally trying to level us all up. But college is often too expensive, many districts are underfunded and outcomes are tied largely to the socioeconomic status of the people near schools. I think those are solvable problems, but there's a bigger issue at the moment.

At some point, and definitely during the pandemic, a loud portion of the population started to question the very science that was going to pull us out of the pandemic. The experts got some things wrong early on, reasonably so given the speed at which it all happened, but applied the scientific method and critical thinking to course correct. Then it got political. Republicans died more from COVID than Democrats by 15%. Since then, some areas are seeing a resurgence in disease because of vaccine skepticism. Conventional, non-fad dietary advice is being tossed out the window in favor of incorrect things people on the Internet say. People insist that they can "do their own research," but they don't understand that research isn't parroting things they find online. Worse yet, and I think this is the thing to fight, is that knowing things and being educated is somehow a sort of elitism. The people we championed in those museums I went to as a kid are, inexplicably, now the bad guys.

We have to reverse this. Being educated and engaging in critical thinking has to be made cool again. There is this swelling sense that we must be the best "again," but I can say with certainty that we can't be the best if we're not willing to do the work. The work is turning out scholars, researchers, doctors, engineers, and yes, even lawyers. Expertise is not a phantom quality produced by conspiracy theories, it's made real by education and commitment to critical thinking. Is that really something that should be controversial?

I saw Bill Nye a few years ago, and he leaned hard into the need for critical thinking. He explained what it is and how to practice it. He has a Masterclass about it. When presented with evidence, we need to potentially modify our world view, even if it is uncomfortable. And that's the weirdest part of it... Science should not be uncomfortable. We do have a shared reality, and feelings will not make reality less real. If the evidence of something comes from a person who has spent their entire life studying, trust their research, because your Google search does not best their decades of experience and knowledge. If they present evidence, it likely can be independently verified.

Education and expertise is important. If we don't embrace that, we will be left behind by the rest of the world. We're already slipping.

1,400 commits to POP Forums

posted by Jeff | Monday, November 18, 2024, 8:40 PM | comments: 0I'm not sure if it's a particularly remarkable milestone, but I made my 1,400th commit to POP Forums since I switched to using Git over Mercurial or Subversion or whatever it was that I was using back then. That was on March 10, 2013, but my first line of code in the post-Active Server Pages days would have been in 2001. I'm not sure when exactly I moved from CodePlex to Github, but probably in 2014. This commit today was to refactor a bunch of poorly named things, and was preceded by a bug that was performing authentication on things it didn't have to. I found it totally by accident, when I noticed that photo grids on CoasterBuzz were slow to load, followed by a ton of Redis cache errors asking for the same data, about the same user. It shouldn't have been looking for those for photos. I'm still curious about why it couldn't accommodate 20 simultaneous calls for the same data, but if I understand that library right, it may make sense. I dunno, the problem is solved, so maybe I don't care about the cache thing.

This serves as a good example of how software is never really "done." At the very least, you have to update the platforms, frameworks and libraries that your stuff runs on. Some of them go away entirely, and the forums have been on three different platforms (technically runtimes, I guess). Heck, it used to be that it could only run on a Windows server, and now it runs in containers on Linux cloud resources. You have to do that updating because eventually whatever it's running on won't be supported, or even available. The frameworks tend to change, sometimes in big ways, which is why that authentication bug crept into the code base.

If you've made it this far, you probably nerd hard, but on the off chance that you're more of a business person who doesn't work in my biz, I hope this makes sense and you take it to heart. You can't just build something once and use it for the rest of time. The longer you wait to update or replace it, the harder it will be. Everyone became acutely aware of this for Y2K, but I think it's time to remind people.

My other motivations include being a performance junkie (pages rendering now in under 30ms), and trying to keep some kind of street cred among coworkers (manager credibility). It also allows me to better understand how hyperfocus works, though unfortunately it seems like it still only switches on if I really, really care about it. It's not that I didn't care about writing code at work back in the day, but the motivation and reason for engagement was different. As a manager I'm context switching constantly, which plays to ADHD strength, I think, but every once in awhile I get in front of something where my architectural advice has been requested, and that switches on the hyperfocus.

I'm gonna try and get v21 out by the end of the year, which is a little later than usual. It won't be a feature-rich release, but there's quite a bit of tuning and organization under the hood that's deeply satisfying.

Finding optimism in disappointment

posted by Jeff | Monday, November 18, 2024, 5:32 PM | comments: 0There are a lot of times in life where we encounter extreme disappointment in people. Like, sometimes I wonder where the heroes are. There are so few people in the world that I look up to, and that's a drag. Those are the folks the I find inspiring. I'm not talking necessarily about famous people, but also folks in your community and profession. I've recently had an overwhelming bout of that disappointment, and that's not even getting into the election where we elected a racist.

To be clear, I'm not suggesting that I'm a hero to anyone, or that I haven't disappointed others. I'm sure that I have. Mind you, I don't want to. I want to enrich the lives of others, not disappoint them. There are a few people who have been very kind in telling me that I have been the opposite of disappointment to them, and for that I'm grateful. It's what makes me want to be good for the world and good for others.

Disappointment comes as a result of missed expectations. Who is setting the expectations is, I suppose, tricky, but many are typical parts of our social fabric. You expect teachers to be kind to children, you expect parents to be interested, doctors to care, bosses to be fair. Sometimes you're just enamored with how well a person does something, only to find in the long run that they're not what you expected.

I've encountered a lot of disappointment lately. It's not a good feeling. But it has also caused me to see others who are more exceptional than perhaps I realized. Obviously the spectrum of non-disappointment is huge, and it relates back to my suggestion that what gives you meaning and purpose doesn't necessarily have to be grand. A lot of small things add up. For that, I find optimism.

Your identity, at risk

posted by Jeff | Sunday, November 17, 2024, 10:15 AM | comments: 0I think it's a reasonable generalization that people spend a lot of time trying to figure out their identity and purpose. Identity can come from a great many things, including your race, gender or ethnicity, work, relationships, hobbies, art... it's probably a long list. Intertwined with identity is purpose, and that's something that can vary in scope from remarkable to everyday typical. Together these may offer a reason to get up in the morning.

Identity can have a lot to do with pride, which is one of trickier human emotions. There are often a lot of reasons that we should be proud of who we are, but it's usually an accepted social contract that one's pride should not come at the expense of others, or be used to make others feel like they're less valuable. Perhaps an unintentional side effect of pride is that others who do not share in your pride may feel excluded. I'm not a psychologist, but my assumption is that not being comfortable in your own identity may contribute to the feeling of exclusion. Not being a part of things doesn't feel good.

On the topic of feeling excluded, I feel like I have more expertise than I'd like. I genuinely feel like I've been a fish out of water most of my life. It's not that I haven't felt safe or secure in any specific place, I just don't feel like I've been a part of any real community. My social circles have always been small, I think maybe four years of my professional career total had me feeling like a part of something, and I'm not really a part of any group. I'd be lying if I said that this never made me sad, but for the most part I understand better than ever what my capacity is for inclusion in any particular group, and I'm good with it. No one is really intentionally excluding me these days.

Being a white, heterosexual male raised Christian in a mostly middle-class family does not really put me in any deep identity category. Sometimes I envy the communities of some of my friends, though some of those communities are necessary because they're marginalized by, well, people like me. Certainly I don't seek to marginalize anyone. My coach and cheerleader tendencies are an important part of my identity, especially in a professional sense. I'm an ally to marginalized groups not because I want to be some kind of white savior, it's just morally the right thing to do. I remember reading in grade school a passage from Martin Luther King Jr.'s "Letter from a Birmingham Jail," and it has had a lasting impression on me.

I must make two honest confessions to you, my Christian and Jewish brothers. First, I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro's great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen's Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to "order" than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: "I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action"; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man's freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a "more convenient season." Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

On the surface, it may seem like he's naming scapegoats here, but when you are part of a marginalized group, it's not by accident, someone is doing it. King's assertion is that the folks on the fence are the ones who can really make change possible. Their apathy only preserves the status quo, or worse, allows us to slip backward.

I don't know if people self-identify as "white moderates" these days. But there are an increasing number of Americans who appears to believe that their identity is at risk of being marginalized. Some portion of white folks are in that pool, and often it includes men of varying races. I think there are several things fueling this. The first is that we seemed to be having a reckoning of civil rights in 2020 during the pandemic. Racially motivated violence, some of it perpetrated by law enforcement, on the heels of the #metoo movement, made it loud and clear that we could not continue to allow inequality to reign. Art forms, especially Hollywood, started to recognize the value of representation in front of and behind the camera. (Mind you, this inclusion just makes more business sense.) Algorithms started to reinforce the idea that all of this desire for equality and representation would come at the expense of white people and men. Whatever identity is carried in being white and/or male was said to be threatened.

Now, it's reasonable to observe that backing anyone into a corner will activate a defensive response. And if there are people who keep telling you that you're being backed into a corner, eventually you start to believe it. It's probably obvious where I'm going with this. The election made it pretty clear that a lot of people felt backed into a corner.

The problem is that it just ain't true, but how do you convince them of that? I'm demographically part of that group, and I can assure you, whatever identity I may have rooted in being a white hetero dude is not at risk. I still have all of the advantages. But being equal with women and people of color does not reduce my standing in the world. The great irony is that there's a backlash against equity and inclusion efforts, because of this belief in a meritocracy. But those equity and inclusion efforts are specifically intended to get us to a meritocracy and ensure that it's real, not reverse the inequity.

I don't know how you fix it. So much of it is rooted in fear and mistrust of people who are different, and when you try to label it for what it is, racism, misogyny, etc., people understandably get defensive. They're backed in a corner. But this is still hate, and it only serves to further marginalize people. People are actually hurt by this. I believe that the morally correct thing to do is to put my own identity aside, understand that it is not at risk, and strive to make others my equal. If you think you're backed into a corner, I invite you to talk to people who are worried about not surviving a traffic stop, or harassed at work for being a woman, or viewed with disgust for who they love. I can empathize with anyone for feeling marginalized, but only if they can engage in the critical thinking to understand whether or not their identity and wellbeing is actually at risk. Unfortunately, that critical thinking has largely given way to beliefs that are not rooted in a shared reality.

Video games have come so far

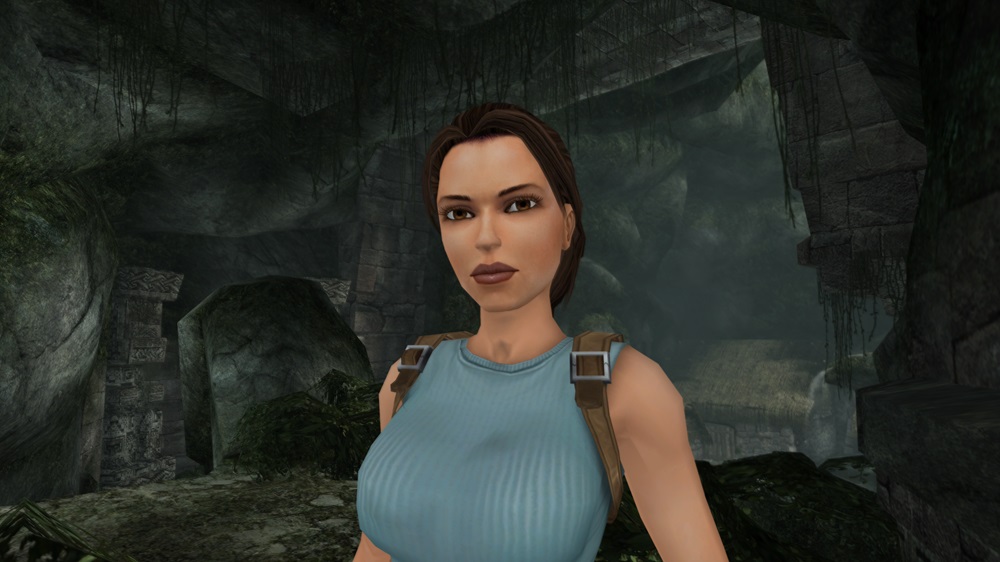

posted by Jeff | Friday, November 15, 2024, 6:21 PM | comments: 0I didn't realize this, but Amazon has a whole gaming thing that comes with your Prime subscription. They have games to play directly like the PC version of Game Pass, and also games via Epic and GOG. The GOG part is super cool, because it comes as redemption codes to own the games forever, and GOG doesn't even enforce DRM. So the other day, the algorithm pointed me at some article that was like, "Tomb Raider Anniversary is free!" What it really meant is that if you were a Prime member, you could get it free via GOG, which obviously I did.

Tomb Raider Anniversary is a remake of the original Tomb Raider game, from 1996, that ran on the first Sony PlayStation. I owned it, and probably everyone did at the time. It was an exciting time for gaming that included the Nintendo N64, and a year or three later, the Sega Dreamcast. But Tomb Raider set a new standard for what consoles could do. Closer to the turn of the century, when dedicated 3D hardware became a thing for PC's, the port of Tomb Raider showed what a PC might be able to do. If you were an enthusiast, you kind of got into the arms race around video cards, to the extend that you could afford it. A company called 3DFX had the best cards, but I couldn't justify the cost. I was on team Rendition, an underdog that actually had solid performance relative to the cost. Tomb Raider was one of the games you used to see how well your rig could run, along with the Quake variants and other shooters. A company called Nvidia also surfaced around that time, and I think you know how that ended.

By the mid-aughts, I mostly got away from PC gaming, since Xbox, PS2/3 and Nintendo Wii came to be. Then with development being better on Macs, I got away from PC's in the general sense. In 2019, I built my first computer in well over a decade, with a high-mid-range video card, and was amazed to play Planet Coaster in 4K at 60 frames per second. Late 2023 I bought the handheld Legion Go, and just last month I bought a PC tower with a ridiculous video card (probably the last time it'll be necessary to buy a huge, water-cooled PC). The distraction and joy to play PC games has been excellent, and well-timed.

Tonight I started up that original, remastered Tomb Raider, and despite the silly modeling of Lara Croft, mostly fixed in the more recent Crystal Dynamix reboot, that quality of the play is actually solid. Sure, there's still weird camera movement at times, and the combat isn't super interesting, but I really appreciate how much this game elevated video games as an art form. In a world with Fallout and Starfield, my expectations for this old game were low, but it's pretty good, even with the (relatively) lower quality of graphics. What's changed the most is scope, certainly. The worlds are now much bigger, and it's possible to mix main line story arcs with countless side quests and potential for explanation. That's why many of these games command budgets larger than a Marvel movie.

Code rot is setting in

posted by Jeff | Thursday, November 14, 2024, 9:58 PM | comments: 0I finally got around to getting package updates and some refactoring I've been meaning to do, and it was harder than it had to be. The refactor was messing with code I wrote possibly as long as 20 years ago. I had it in my head, long before I would actually run stuff in the cloud, that I would need to figure out how to cache bust settings when they changed across nodes. This is a solved problem in a general sense, but the settings were different because I store them as a bunch of rows of key-value pairs, all text. So to load them, after they're fetched from the database (or cache), the code has to cycle through them all and convert them to integers or booleans or whatever as necessary. I obviously don't want to do that on every settings call, which happens a lot. I was also doing singletons wrong, from before dependency injection was ever really on my radar. Yeah, this stuff was ancient.

The other thing is that .Net v9 was just released, so I'm trying to update the many packages and such for that. It's not going super well. As usual, the Azure Functions project, which does background stuff like reindex topics for search, is broken as hell. For some reason it won't map all of the dependencies. There's no obvious reason. All of the tooling around functions has been substandard for years, and it's frustrating. But when it's running, it's great because it runs tens of thousands of times a month for a few pennies, not bogging down the web app.

It's just a lot to change at once, and I should know better letting it rot for so long. On the positive side, all of my build and deploy pipelines are working like a champ. That saves so much time.

Everything you've learned is wrong

posted by Jeff | Thursday, November 14, 2024, 9:55 AM | comments: 0Life teaches us a great many things.

I would imagine that one of the earliest things I had to learn was that we shouldn't lie. There's no context really when you're not even in school yet, but we grow up to understand that lying creates mistrust and reflects poorly on us. Related, we learn to be faithful to our partners, or at the very least, honest with them. We learn that we should honor those who serve our country. We learn that we should respect experts, like doctors, scientists, lawyers, because they spend more time in school than most of us, and they have to commit to a lifetime of learning. We learn that racism is particularly heinous, though many of us have to arrive there ourselves when it isn't taught by our elders. Hopefully we learn to be charitable and kind to others. We learn to offer grace and dignity to people who are less able-bodied than us. We learn that there are consequences for violating the law.

These are just some of the basic social contracts that we adhere to as moral Americans.

And if you voted for Trump, you're saying that none of those things actually matter. In fact, being the opposite of all of those things qualifies you to be president. How do you explain that to a child?

You are hurting people that I care about

posted by Jeff | Friday, November 8, 2024, 12:30 PM | comments: 0I recall a lot of feelings eight years ago about the cognitive disconnect between character, morals and reflective honesty among people who voted for Trump. We had the racism, misogyny, xenophobia and such then, but now we also have the felonies, enlisted people who are "suckers and losers," being held liable for sexual assault and libel, leading an insurrection, desire to be a dictator, wanting to "suspend" the Constitution, being pals with our enemies, etc. As much as I'd love people to look me in the eye and explain how they justify it (I think you already know that they can't), there's a more fundamental problem that's even more personal.

I can be honest, as a hetero white guy who can afford things, I am not in significant cultural or economic danger. The thing that keeps me up at night is the people that I care about. Half of them are women, but they're also immigrants, people of color, non-Christians, LGBTQ, children. They're coworkers, friends, friends of my son, neighbors, people in communities that I'm a part of. They've all been victims of increasing levels of targeted hate speech that has been getting worse all year. This week it has spiked to astronomical levels, as Black people via text and on Twitter are getting "@s" telling them to report to plantations. Jews, Asians and Latinos are being threatened and told to leave the country, and I saw an actual tweet from a guy who said, "I can fuck whoever I want and get away with it."

Had the election gone the other way, the MAGA folks would exist in the next four years as they did the last four years, which is to say better off on average. Every real statistic validates this. Instead, regardless of what policy may actually occur, the people that I care about will face real danger, discrimination and quality of life issues. It's already happening.

So look me in the eye, without hate, and explain to me why you don't care if people that are important to me will be hurt. Explain to my kid why that queer friend at school shouldn't be scared.

I can't explain America to my child

posted by Jeff | Wednesday, November 6, 2024, 10:54 AM | comments: 0It's hardly a secret that Simon is a little different. We have that in common. We have both had to deal with bullies, had difficulty finding "our" people, and we've watched people in our social circles become casualties of a world that fears different. Before he left for school this morning, I woke to hear him saying, "How can Trump win?" He's seen enough of the guy on TV to understand how hateful he is. Kids can see it pretty obviously.

But I can't answer his question. I can't explain it. For me at least, it's the classic unreconcilable autism moment. I can't explain a world that rejects critical thinking, science, expertise, civil discourse, equality and the law. American sentiment toward its government, at a time when almost every objective measurement shows things moving in the right direction, overwhelmingly rejects that measurement. And while Harris could certainly be faulted for a great many things, it doesn't change the fact that right and wrong exist. It is the difference between a felon and a prosecutor, literally.

As I've contemplated some kind of explainer, more and more, I'm having to accept a reality that I've been rejecting myself for more than a decade. The United States is a racist and misogynistic country. Trump is, objectively, and by definition, a racist and misogynist. The problem is that half of America doesn't care. Over and over again, it has marginalized its own people. It started with Black people and women. Then it was immigrants from Ireland, Italy and Greece. Then it doubled down on classic racism. Then it was Asians, east and south, the Middle Eastern folks, Jews, Muslims, and more than ever Latinos, despite being a significant portion of the population. And of course, LGBTQ folks have been bearing the brunt of hate for all of American history.

I still, probably naively, hang on to some kind of hope. Like a lot of people, I'm sure that art is where I root that. In the TV show The Newsroom, Sorkin writes a monologue for the lead where he explains how not awesome we actually are:

Just in case you accidentally wander into a voting booth one day, there are some things you should know, and one of them is there is absolutely no evidence to support the statement that we’re the greatest country in the world. We’re seventh in literacy, 27th in math, 22nd in science, 49th in life expectancy, 178th in infant mortality, third in median household income, number four in labor force, and number four in exports. We lead the world in only three categories: Number of incarcerated citizens per capita, number of adults who believe angels are real, and defense spending where we spend more than the next 26 countries combined, 25 of whom are allies. Now, none of this is the fault of a 20-year- old college student, but you nonetheless are without a doubt a member of the worst period generation period ever period. So when you ask what makes us the greatest country in the world, I don’t know what the fuck you’re talking about. Yosemite?

But with that, he pivots:

We sure used to be. We stood up for what was right. We fought for moral reasons. We passed laws, struck down laws for moral reasons. We waged wars on poverty, not poor people. We sacrificed. We cared about our neighbors. We put our money where our mouths were and we never beat our chest. We built great big things, made ungodly technological advances, explored the universe, cured diseases, and we cultivated the world’s greatest artists and the world’s greatest economy. We reached for the stars, acted like men. We aspired to intelligence. We didn’t belittle it. It didn’t make us feel inferior. We didn’t identify ourselves by who we voted for in the last election and we didn’t–we didn’t scare so easy. Huh. Ahem, we were able to be all these things and do all these things because we were informed. By great men, men who were revered. The first step in solving any problem is recognizing there is one. America is not the greatest country in the world anymore.

I'm willing to admit there's a problem. It's all I've got. It makes me incredibly sad, because it doesn't have to be this way. We're being tested, and at a point in my life where I'm so tired of the test. People that I care about are going to get hurt. The people who want to hurt them have been empowered. It's not a good time to be different.