Archive: August, 2021

An empathetic connection

posted by Jeff | Tuesday, August 31, 2021, 9:54 PM | comments: 0The strangest observation that I could make about humans is that intelligence is often disconnected from all of the other things we do. I was talking with my therapist today about the fact that I can't easily apply my professional skills to my personal life. Similarly, I'm pretty good at counseling others in certain situations, while often incapable of seeing my own situations for what they are. When it comes to Simon, as smart as he can be about things that interest him, he doesn't connect the dots between other things.

We've always struggled with getting Simon to follow directions. I'm guilty of the same thing, and it's easy for others to conclude that I think I'm simply smarter than the directives. But the real underlying thing is that we simply can't reconcile the desired outcomes as necessary. That's not a function of ego or arrogance, it just doesn't add up. What I know as an adult is that this situational context that we seek may be irrelevant, but for an 11-year-old kid with ASD, the lack of context simply makes understanding the directive less likely. Unfortunately, as a parent this is concerning because often the directive could be a safety issue, and there's no time for negotiation.

The other night, Simon was smothering one of the cats on the table behind the couch. You know how this goes... the cat eventually starts to squirm away. In this case, we asked him to stop also because there's a lamp on that table, that he and the cat were pushing against. If you guessed that the lamp got pushed off the table, broke in several places and left a dent in the floor, you'd be correct.

My initial response was anger, and I declared TV time over, and it was time to get ready for bed. He cried, ran up to his room and slammed the door. We've been through situations like this before, and I knew where his head was. The cause and effect of not following directions was not on his mind, but you can bet he was stuck on the broken lamp and losing TV time. The frustration as a parent of not getting to the underlying problem is exhausting, but for whatever reason, I was unusually calm about trying to get there.

When I went in to talk to him, it was immediately, "I'll buy a new lamp!" in between the tears. I calmly explained that I didn't care about the lamp, and came up with some arbitrary example of why not following directions has consequences. His response was pretty intense yelling about not talking to him and leaving his room. Honestly, I didn't have the energy. Work was difficult that day, and I was spent. I just told him I was done, good night and we'll talk another time.

That's when something unexpected happened. He tried to physically stop me from leaving, not with pushing, but hugging. He desperately said, "No, Daddy, I want you to talk to me." I had seen this movie over and over again, and this is not how it ended. I asked him to look at me and listen, and I explained to him, "I'm very worried about your safety, that one of these days you won't follow directions and get seriously hurt." He just looked at me, said, "OK," and leaned in for more hugging.

Here's why this was a big deal. What I observed was that, maybe for the first time, despite his own difficulty in managing his emotions, he seemed to see and understand where my emotions were. Usually at this point, he's just looking for one of us to help him calm down, but his body language and eye contact seemed to imply that, at least for a moment, he made it about me.

To Simon's credit, I've seen him act this way a bit more in the last year when he wasn't under stress. Between Diana's back pain problems and my mental fatigue around a number of challenging things, he has checked in at times. What gives me hope is that we're starting to see the thing that I recall one of his doctors talking about early on, that kids often build the coping skills to compensate for different wiring in their middle school and high school years.

Is this a solved problem? Nah, we will go through this again. But it feels like a victory, like forward momentum. I'm very thankful for that moment.

All of that stuff about bravery isn't bravery

posted by Jeff | Sunday, August 29, 2021, 10:39 PM | comments: 0Self-help and cheerleading is an enormous business, but it's also something a great many people commit to as a means of self-improvement. That makes a lot of sense, because at the end of the day, only you can really improve you. However, I think we view it in a way that seems kind of silly once you get a little older.

If I look at 20- and 30-something me, I often looked up to people who seemed "brave" and willing to take risks to do stuff and better their situations. I'm sure I encouraged myself to engage in this sort of bravery, too. I'm sure I can find instances of myself opening up with the greatest vulnerability about my perceived weaknesses, and boldly declaring that I was going to be brave and take a chance to make myself better. (For real, this was Live Journal and MySpace in the early aughts!)

What I really didn't get back then is that the stakes weren't really that high. I think that there are slightly embarrassing elements of narcissism, hyperbole and self-righteousness there to believe that you're really being brave for that big change or that bold move you were going to take. (I mean, unless you're actually doing something that puts your life at risk.) I'm not trivializing the act of making important decisions, or overcoming the discomfort often required for such acts, I'm just saying there wasn't that much at stake.

Now, over 40, you would think that I would take things even more seriously, with a wife and a (sometimes challenging) child, but no, there's still not a lot at stake. In the last 12 years or so, I've made all kinds of "brave" moves, but as I'm often fond of saying, nothing is permanent. The big thing we seem to ignore is that few doors are one-way. We can reverse most decisions. Sure, there are consequences, but that's part of the calculus of any decision.

I remember how I felt when I decided to pursue a technology career and abandon the broadcast world. It was a big deal, and it worked out for me, but there was nothing really at stake there. Moving all over the damn place in a span of a few years wasn't really the big risk it may have felt like. I mean, I did get fired once, which didn't matter.

So to my younger self, or all the people who are younger now, you may feel like you're taking great risks, but honestly, they're probably not. All of that stress and anxiety that you're feeling over the big decisions is probably not serving you. What doesn't work out will probably lead to something else.

What will you do about the hardest problems?

posted by Jeff | Sunday, August 29, 2021, 9:54 PM | comments: 0As terrible as the last year has been, I think we have seen a lot of examples of people at their absolute best. It's certainly disheartening that we've also seen the opposite, but overall it inspires me to see what people are capable of when they're seriously challenged. It makes me want to be a better person.

Indeed, we have many serious challenges ahead, and I don't think that solving them is optional. Again, it can be hard to see a world where we succeed, especially as we try to get beyond this pandemic. Science offered us some reasonable solutions to control the spread of Covid, even if they were a little awkward, and then it led to a long-term solution in the vaccines. I don't think the ask for masks and social distancing or vaccination were a very hard lift. The latter is probably the easiest thing I have ever done that would positively affect countless other people. But a significant portion of Americans failed to do that easy thing, and here in Florida, we're worse off than we were before.

I could be a real Debbie Downer about the whole thing, and reasonably so given the context. I can't remember seeing as much selfishness and willful ignorance at any other time in my life. How can we expect people to do the things that are actually hard? But underneath all of that nonsense, I see a quiet persistence by many people, a part of me hopes it's most people, to take on the hard problems. The question is, what role will we play?

Climate change

Climate change feels like the hardest thing to take on, in part because the effects of it vary in severity depending on where you are. They can also be seasonal. The math is not encouraging, as we keep breaking records for hottest year, and new regional daily temperature records at both extremes. Six of the top 10 years for named storms are in the last 20 years, with a clear trend line going up. The ocean is coming up through the ground in Miami. Even the US Department of Defense has named climate change a credible threat to world stability, as it forces migration and destabilizes economies. Oh, and air pollution kills more than 3 million people per year.

Trying to have an impact on the reduction of greenhouse gases isn't straight forward, because you can't entirely control where your energy is coming from. We're all in with solar on the roof, and we've been driving electric vehicles exclusively since 2015. However, solar is a somewhat large investment up front, and EV's aren't quite where they need to be in terms of price to increase the rate of adoption. The market itself though is starting to turn things at the utility scale in the right direction. The actual cost of renewables is now generally less than fossil fuels, so utilities will certainly start leaning in that direction.

The problems is that the US, EU and China all pour trillions of dollars in subsidies to the fossil fuel industry. In the US, much of this includes insane tax advantages that encourage capital investment in drilling and mining. As taxpayers, we can remind our elected officials that this is not sustainable, and encourage them to redirect these subsidies to renewables (or eliminate them entirely). We can not vote for those who are themselves propped up by these industries.

Racism

I think if the last year has taught us anything, it's that it isn't enough to not be racist, which is neutral, we all have to take a role in being anti-racist. That means that we don't simply sit on the sidelines, we have to get involved and speak out against things that are racist. That isn't some function of "wokeness" or whatever, it's accepting that racism is not simply white people acting out against people of color. Our societal systems have engrained racism in ways that we either overlook or simple forgot about. We have to understand our history, which doesn't mean taking responsibility for it, but rather to change its outcomes today. I wasn't there for redlining, but I know what it is. I wasn't there for Jim Crow, but I know what it is, and I see it happening again with voter suppression. I know what it means when people pass over the resumes of people with "not white sounding" names. There are so many subtle things. If we listen, and we learn about them, we can be anti-racist in our actions.

A huge portion of this is teaching your kids to be anti-racist. You must instill in them the courage to speak out against discriminatory acts. Teach them about our history, because I can promise you they'll never get to it in school. Be what you want them to be, because they're watching you.

Healthcare

I have arguably the best healthcare insurance. I don't have to pay for any of it, and then there's a reimbursement account to catch all of the deductibles and co-pays. Despite this, we routinely have to spend time on the phone resolving billing problems with insurance. Recently, we even had the insurance company deny an MRI ordered by Diana's neurologist, which means that the doctor is not in charge of her care, some arbitrary schmuck is. This is what the "best" looks like in America. Tell me more about the "freedom" this system gives you! Because without a job, you don't have insurance, and if you don't have insurance, you don't have healthcare.

We're in the best of circumstances, so it's safe to assume that the scene is significantly worse for everyone. Part-time or gig workers are lucky to have access to a plan at all, even through the feds, and you can be sure that the co-pays mean a choice between getting care and paying rent or buying food, so they go without the care. We've seen this play out in countless negative ways, especially for children. The entire system is immoral and unfair, despite having the science to preserve and improve life. It's also a thing that my friends in the UK and Norway say they have never had to worry about in their home countries.

I tend to be fairly practical in my politics, but this is one area where the idealist progressives are the only ones with the right idea. There should be a single-payer system. If you need healthcare, you get it, and that's the whole process. No more skipping because you can't afford it, or being denied for something by bureaucrats. Will it end the insurance industry and put people out of work? Yes, and I don't care. I spent a year in that machine, and that was too long. We're the last developed nation in the world to not adopt a system like this, and our outcomes, in life expectancy, infant mortality, obesity and chronic illness rank at the bottom of the list. We have to do better.

Bonus hard thing: Less work to do

I'm not sure how to define this, let alone solve for it, but the reality that we've been kind of ignoring for decades is that as technology continues to evolve, there is less for humans to do. Yes, it's the Wall-E scenario, where everyone gets fat and floats around on hover chairs because there's nothing for them to do. I'm not sure it looks like a preachy Pixar movie, exactly, but we seem to be ignoring that it's already headed in that direction. It takes fewer humans than ever to make physical things. As I've been saying for years, jobs where a human has to drive a vehicle will completely go away when the trucks drive themselves.

The reason this is so hard to address is because the only thing we know is the myth of meritocracy, the idea that if you work hard enough you can achieve anything. We know that this is bullshit, because not all people are equal, but people still use this as the intellectual basis for the way we treat work and its place in our society. I know people who have killed themselves for work just to get by, and others who haven't done much of anything and thrived.

I don't know how we solve this one, on a planet where we already allow poverty to occur, but it's going to get slowly get worse. I mean, much of my career has been spent building things that optimize things that were once a manual human process. The good old days of landing at a company and working there for 40 years are long gone, and they're not coming back.

Scope

I've said this a lot the last few years, and I'll say it again: The scope of your involvement and contribution is not something to get hung up on. You can help solve these problems with the smallest of gestures and actions. You can also allow them to get worse by not acting at all. Please help. We should leave this joint in better shape than we found it.

He made a thing. This is what happened next.

posted by Jeff | Thursday, August 26, 2021, 11:22 PM | comments: 0I've always enjoyed making stuff one would generally call "content," which I would call "media" before that Internet took off. Writing, video, audio, photographs and such. I've told the story before about how this enjoyment is what led to the creation of Guide to The Point then CoasterBuzz. In those early Internet days, or even when my programming book was released in 2005, stuff that was useful or of a certain quality would generally bubble up to the top.

I am notoriously critical of how much crap is on YouTube, but one of the excellent science guys recently explained why click bait works, though making some differentiation on what is legit, and what isn't. Now add in the algorithms of social media platforms, which we know are all about driving "engagement," and not so much leading you to the "best" or highest quality things. What's so crazy about this is that the Internet was supposed to level the playing field because fundamentally, anyone can put something online, all on the same Internet, but because we've become so reliant on these platforms, that's not actually what happens. None of this works quite as well as human curation does.

When I first started to publish stuff online, the only advantage that I really had was a first mover advantage. That probably doesn't matter as much in a niche content area, but it helped. I have stuff that endures while countless things have come and gone in 20 years. But trying to start something new is a daunting and unpleasant task. You have to play that click bait game, and worse, you have to "build a brand" in the social ecosystem, which again is intended to drive engagement, which to me smells like inauthenticity. As Derek, the Veritasium guy said, this is literally half of the work involved to run a popular YouTube channel. And the thing that I find even more distressing is that all of the people who have found traction are fully reliant on platforms that could disappear tomorrow, or decide that they're not going to distribute their content. That's horrifying.

I want to make things and put them on the Internet, but I have no interest in all of the above. I think it all sounds exhausting. That's a tough spot, because I could completely disregard all of that nonsense, but I do want someone to see what I've done. I made some videos at the beginning of the year, but I'm pretty sure only my friends have seen them. I don't care if they're good or not, it's just something I wanted to try. I want to try and do some others too, but I am uninterested in all of the bullshit to game the system to get clicks. I mean, I'm not posting these on YouTube because I think I can get to the subscriber and hour counts, I post them there because it's where the people are. Otherwise, I'd be happy to pay Vimeo to put them on their service.

At this point, I have to resolve that I'll put new things online mostly for my own amusement. If I reach a certain bar of quality, that will be nice, but I can't expect the quality to result in clicks. The rest just doesn't seem fun.

The "right thing" for creative fulfillment is a false choice

posted by Jeff | Sunday, August 22, 2021, 9:34 PM | comments: 0Adam Savage, of Mythbusters fame, recently talked about how his hobby as work exercised the creative muscles that satisfied him personally and in his career. That led to something of an epiphany for me.

I have long admired the folks that work in theater or film, for the satisfaction that they have that their work has led to deeply satisfying results for the people that they serve. We were watching the latest episode of Ted Lasso this weekend, for example, and I though, what a gift to be a part of something like that. It's why I buy video equipment and hate myself for not writing something that would result in filmmaking.

But I'm starting to realize that the absence of my participation in such endeavors does not mean that I'm failing. I'm coming off of a particularly difficult week at work, where some things went down that were less than ideal. But the thing that I overlook in this case is that I'm still part of a larger team that enables some pretty amazing results in a growing business that benefits millions of people. It's not the same as being a part of an Emmy-nominated TV show, but that doesn't mean that it isn't important.

The reality is that the thing that I do get to do doesn't mean that I have somehow failed for not being able to do the thing that I recreationally dream about doing. This is the false choice often forced by the "pursuit of happiness" that we're supposed to chase. I could still do the thing that I believe will give me a higher level of satisfaction in life, but it doesn't mean that the thing I'm already doing isn't already pretty awesome.

There is definitely a separate issue of where things rank when the years have gone by and you're taking inventory. For me, some jobs were more meaningful than others, and certainly some things even from my spare time will mean more than others. I'm still not sure anything other than parenting itself will outrank coaching for me. But as far as our contentment goes in daily life, there is certainly a continuum, and I'm starting to see that the status quo is already pretty good even if it isn't the thing you might dream of. It's not a compromise to believe that, it's just the truth.

I want to have a (small) party

posted by Jeff | Sunday, August 22, 2021, 6:54 PM | comments: 0One of my big self-exploring conclusions in these strange times has been that I really like people, sort of. My therapist recently asked me if I would consider myself an introvert or extrovert, and I responded that I'm very much an ambivert, which is to say, it depends. I am good getting in the mix when it serves me, which I would say includes hosting a party, speaking at a conference, interviewing for a job, etc. What isn't obvious in those situations is how spent I am after it's over. I legitimately enjoy it in the moment, but it really takes a lot out of me. And I have to come back to the part about it serving me. If it's a situation that does not serve me, say, going to some random club or party where I don't know people, that's not my thing.

As vaccination started to ramp up in the spring, Diana and I were thinking, we need to have a serious get-together when the time is appropriate. We were thinking, let's do it right, catered party, maybe with entertainment. Maybe it's our holiday party. The bottom line is that we need to celebrate life with the humans that we appreciate.

Now, I'm not sure if we even can, because fucking Florida. Simon is not vaccinated. While I appreciate the relative risk to my son, both in terms of likely Covid infection and severity, that's not the kind of risk I'm crazy about. With Governor Fuckwit basically banning self-rule when it comes to public health, we're in a literal hot zone of stupidity and disease. If you invite 20 vaccinated people, there's a good chance that one could be infected even if they're all vaccinated. Does that seem impossible? No, because one of the people we would invite did not vaccinate, and he's fighting for his life right now in the hospital. His odds aren't good.

I'm endlessly frustrated with this situation. We have a solution, as one of the richest nations in the world, and we've completely fucked it up while poor nations are being beat up with Covid. It's hard to have faith in your own nation when it can't do the simplest of things, provided to them, to get a shot. As fucked up and inefficient as our system of healthcare is, we had something straight forward and relatively easy, and we can't even get it done. Can you imagine having something genuinely hard to deal with, like a war on our own soil, or shortages of resources? We would without question descend into chaos, because we can't even do the simple thing. The loudest voices against Covid mitigation are ironically against all of the things that make moving past it possible.

Maybe this will start to burn itself out, and a holiday party will be possible. Maybe we'll get youth vaccinations approved before then. I want to have a party.

Software at scale

posted by Jeff | Saturday, August 21, 2021, 7:11 PM | comments: 0As part of my parting words of advice to our interns a couple of weeks ago, I told them that the scale of what they do is all relative, and larger doesn't necessarily mean better. I do believe that, but it's interesting to find myself working with a bunch of engineers who make stuff to handle an enormous amount of commerce. In some ways, I'm happy to defer the actual code writing to them, although managing the process involves all kinds of different challenges. I though I would never see large scale again after working on the MSDN Forums back in the day, but here I am again in the middle of something even bigger.

Conversely, even with a nice 20% bump in traffic over last year (and more than three times the revenue), my sites are pretty small potatoes by comparison. Over the years, I've tweaked and tuned all of that stuff, and it's not likely to ever see traffic serious enough to test it. It's total overkill to apply all I've learned to a couple of goofy sites about amusement parks. Most of what I do these days is try to make sure that it all evolves with the technology so it doesn't become something old and crusty that can't be maintained.

The other night I actually made my first commit in months. I have been (very) slowly trying to get rid of all the old jQuery stuff, responsible for some of the dynamic junk in the forums. Javascript itself has made it not very necessary, and Bootstrap, the framework I use as the style base, no longer has a dependency on it. It's a lot of refactoring in the area that I'm weakest in, the front-end stuff.

But again, I think my point about the scale is legitimate. The output of it is important to someone regardless of the scale.

The Covid hospital crisis is real, and it's happening here

posted by Jeff | Wednesday, August 18, 2021, 10:26 PM | comments: 0We've all seen the tents set up in parking lots and the refrigerated trucks being used as morgues at hospitals during the previous Covid case spikes. Those two periods of time were preceded by a general relaxing posture toward mitigating the disease, despite warnings. The outcomes were not unexpected. Once the vaccines started to reach general availability for adults, the relaxation started again, but this time, it felt justified. We had an out, and it was glorious and powerful.

But not everyone played along.

Here in Florida, only 51% of people are fully vaccinated, so when you're out in the world, half the people you encounter are not fully vaccinated, but everyone is acting as if the pandemic is over. You know what happened next. The state has 50% more cases than in the peak of last winter. The death count is about the same so far. The real issue though is that hospitalizations have doubled since the winter peak. There are 1,500 people in Orange County hospitalized with Covid, and zero ICU beds available.

A friend ended up going to the ER last weekend after a serious cut to her knee, as it clearly needed stitches. The lobby was full of people waiting. The receptionist asked her to wait behind the desk with her, to stay away from everyone else who was assumed to be infected with Covid. There were no treatment rooms available, so a nurse practitioner did her best to get her set up on a random counter, where she did the stitches. The nurse confirmed that the hospital was full, and about half of the patients were there for Covid, all of them unvaccinated.

The downstream effect of this is that there is a limit to the amount of care, and therefore the quality, and it doesn't just affect the Covid patients. If you come in there for a heart attack, you may not get the level of care you would ordinarily get. Diagnostic procedures may be delayed. We're having the meltdown we were trying to avoid, and it was totally preventable. I'm frustrated to no end that all of the people who were protesting over haircuts and bar visits could have done the work to make it safe and low risk for all of us, and empowering the economy in the process.

Anecdotally, it appears that vaccination rates are headed up, and I really hope that's the case. I never thought it would be a hospital in my own neighborhood that was in trouble.

A cat adoption story

posted by Jeff | Wednesday, August 18, 2021, 9:30 AM | comments: 0The addition of Finn and Poe, our big furry ragdoll cats, was easily the highlight of a difficult year. They are very nearly perfect cats. We were very set on getting that breed in part because of my brother-in-law's wonderful cats. I don't entirely understand how genetics can make an animal predisposed to have certain personality traits, but they are the most chilled out, affectionate cats I've ever had. While there's certainly some amount of guilt from having "designer" cats instead of those from a shelter, I'm at that place in life where I don't know how many more cats I'm going to have, so I wanted what I wanted, and don't regret that decision.

When Diana and I started to cohabitate, she had three cats, and I was down to one. That foursome moved to Seattle and back with us in the car (solo with me, on the way back), and then the surviving three came down with me to Florida. We're used to having a large pride. After we unfortunately lost both Emma and Oliver last year, I was content to just have two. Diana had other plans.

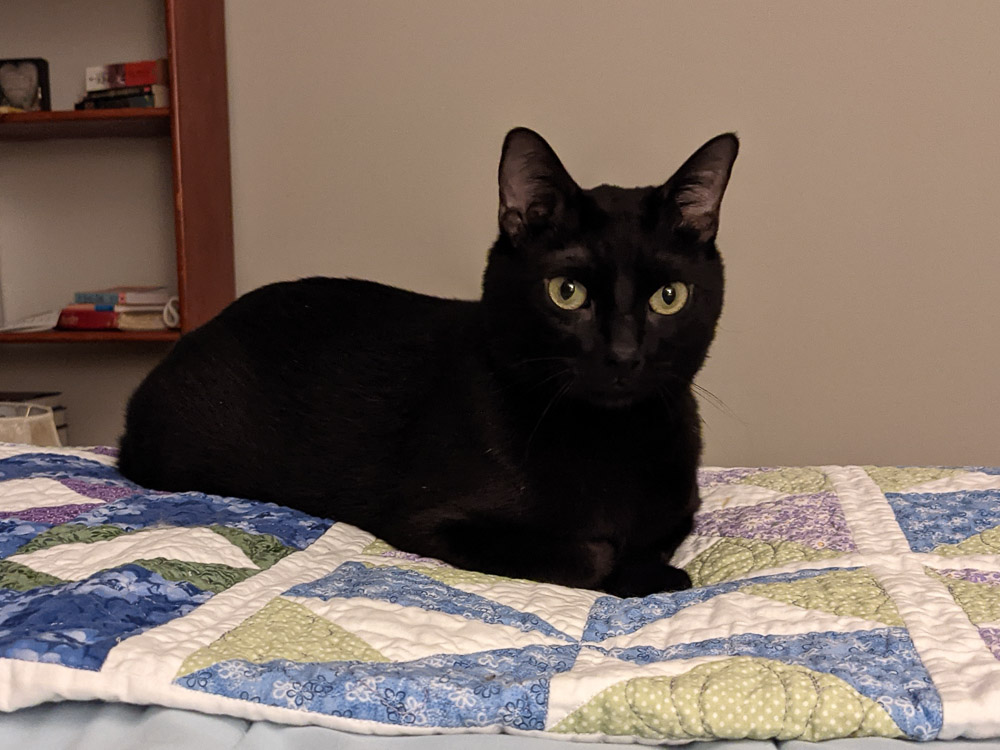

She has been volunteering at a local pet store that hosts a cat adoption service. She's always had a thing for black cats, and I would say that our giant Gideon was one of our favorites. She learned about this 3-year-old, going by "Rummy" or something like that, close enough to "Remy," who was being fostered through this organization, and he was looking for a permanent home. Given the no-risk nature of this, we gave him a shot.

Starting in the guest room, he was a very nervous animal that mostly wanted to hide, but if you were still for a bit and just quietly hung out, he would come visit you. He was very affectionate, ready for the rubs where ever you were ready to give them. His nervousness seemed extreme, but he didn't hate me or the other humans in the house. That was a good sign.

Things didn't go as well with Finn and Poe. Finn immediately took to hissing at him, which was disturbing because we've never heard him make that sound. He's a lover, not a fighter, and often on the bottom of the wrestle pile with Poe, despite being the larger of the two. Eventually what we saw was Remy chasing the other two cats, who suddenly were taking cover under our bed in a way not characteristic of their typical behavior. The situation didn't get better over the course of a week. It turned out that Remy was very sweet to humans, but he was not meant to be a part of a multi-cat household.

Diana reluctantly brought him back to the store on one of her volunteer shifts. Fortunately, the story did not end there. A family with three kids and no cats came in looking for a special cat, and Remy warmed up to one of them almost instantly. Diana pitched him as a friendly little buddy, which he is, provided you don't get any additional cats. She went back to the store that evening to meet the family again, with the dad, and Remy had a new home.

I'm happy that the story had a happy ending. Simon was a little sad that he didn't get a chance to see him one more time, as he sometimes helps volunteer, but we're all glad that he has a home. Non-kittens are sometimes hard to place, but this little guy, nervous as he was, no doubt will make a great pet for the family.

On the levothyroxine

posted by Jeff | Monday, August 16, 2021, 9:54 PM | comments: 0A few days into taking levothyroxine for the subclinical hypothyroidism has been super weird, to say the least. The first morning, I was hungry in a way that I can't recently recall within about two hours. We were at Animal Kingdom for one last outing before school started, and I had about half of a cinnamon roll. To say that I was super alert would be an understatement. By 11, I crashed super hard, to the point I was contemplating going back to the car for a nap. I was fine once I had lunch. Sure, the pastry is pretty much all sugar, but I'm not used to feeling anything like that.

The second day was similar, but the swings weren't so extreme. Today, the third day, it was tough to get to 11 before eating, but I was only a little tired after lunch. I actually powered through some writing for work in the late afternoon. Maybe tomorrow will feel more normal. If the morning hunger persists, I may have to figure out if I can start eating breakfast again, which I mostly stopped doing late in 2019.

In the mean time, I've been reading more about the science and downstream effects, specifically around metabolism and cholesterol. Looking at my weight and previous labs, I wonder if things started to change over the course of 2018, because that's when both started drifting upward without any specific behavior changes that I can nail down. I blame emotional eating on some of it late last year, but I'm starting to learn that it may be oversimplifying things to blame it on one thing or another.

While I'm getting comfortable with what the treatment is and its potential, I'd be lying if I said this hasn't head-spiraled me into a world of ideas about might end me prematurely. I mean, I wake up with a slightly sore throat (because that's next to my thyroid), and I wonder if it's throat cancer. It's absurdly fatalistic, but it just seems like the universe's way of fucking with me now that I'm starting to really work through my shit and be content in ways I had not previously known. And yeah, I'm the guy who thinks fate is bullshit.

Anyway, the stuff doesn't work in one day for most people, so off we go.

The importance of authenticity

posted by Jeff | Sunday, August 15, 2021, 7:54 PM | comments: 0I've noticed that the issue of authenticity has come up a lot in the last few months in therapy. It's not entirely surprising, because as you enter midlife, I think one typically takes on the process of measuring what's important in life. You're looking for meaning, trying to prioritize and optimize what gets your attention, based on a combination of life experience and maybe some acknowledgment that you may have more time behind you than in front of you.

What does it mean to be authentic? To me, it's someone who is true to themselves but also in a way that you might perceive to be "good." I wouldn't strictly say that it's someone who gives no shits about what others think, but that's a component of it. Maybe it's someone who isn't conforming to a certain box or set of expectations, and definitely not someone who is showy for the purpose of validation or attention.

I admire authenticity, but it seems largely missing from our culture. Reality TV and social media have turned attention whoring into a sport, and people are quite literally famous for being famous. One can be an "influencer" without actually doing anything of value. People invest more time in selling themselves than anything else. Some believe that they can have expertise without doing the work to be authoritative by experience.

It's not entirely bad that everyone has to have a blog and a podcast, because some people who do that are authentic in their experience, communication and intent. That's even true on TV, sometimes (see the show Home Work on Magnolia/Discovery+ right now, I love it). You can even find legit people on YouTube, which is often a wasteland of contrived nonsense.

Diana is among the most authentic people I know. She's always been what she wanted to be, and at the same time kind and generous. She has never perfectly fit into the boxes of societal expectations or any of the roles associated with any of it. She has professionally done the things she wanted as long as they suited her. Her commitment to parenthood has been extraordinary. She's also a cat person, so hard to go wrong there.

Authenticity has never come easy to me. In high school, I desperately wanted to fit in, and worried about what everyone else thought of me. In college, I did a lot of the same, at least until my senior year when I was basically over college. Professionally, in broadcast stuff I was always posturing, and in software I intermittently was chasing dollars instead of leaning on the things that I was good at. There were piercings I didn't get because of what I feared others might think.

On the other hand, I've never bothered to buy a suit, and I've generally been willing to call things as I see them (pretty sure these might be related to autism, not authenticity). I thought I was a pretty good volleyball coach, vulnerable about my own ability while wanting the best possible outcomes for my kids. I've spent a lot of time in the last few years really trying to understand my place in the greater order of things, how I can best contribute, and above all, be OK with who I am. I want to be kind and helpful, and also maintain boundaries. I want to maintain my privacy, but the parts I show people will not be fake. (Not those parts, you pervert.)

If my introduction to midlife is teaching me anything, it's that there isn't a lot of time for bullshit. That seems like a good way to summarize where I am in life.

Hypothyroidism

posted by Jeff | Thursday, August 12, 2021, 7:37 PM | comments: 0Well, yesterday's post about good and bad in constant battle reinforced that illogical theory. This morning's follow-up with my doctor after the labs were processed revealed that I need to start taking meds for hypothyroidism. That's completely terrifying, and just what I needed before a particularly challenging day at work.

Of course I spent some time decoding what this means, but my doctor did a pretty good job of explaining the basics. Your thyroid makes hormones that controls all kinds of things, and tends to have a lot of influence on your cholesterol and weight, both of which are high. It tends to influence your general energy level and often depression as well. While I've never been in the "here come the diabeetus" range, all of the above have been out of normal range pretty much since I turned 40. Looking back at previous labs, I also wonder why I've never been tested for this since the recommended screening age is 35. The treatment is to take a synthetic hormone daily, and I could notice a difference in a day or two.

So while that's all terrifying, it's also interesting because it could pretty much be a treatment for everything else I've struggled to keep in the normal range. It's also a solid "fuck you" to the non-doctors that sell you the bullshit that you can get there if you just want it bad enough. I've become very sensitive to all of the non-expert advice for health out in the world these days, and this just reinforces that.

It might be a long six weeks to the follow-up though, because of course researching the medical literature creates as many questions as it does answers. The primary measurement of concern is TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone), and the top of the normal range, per my doctor, is 4.5 mlU/L. Mine came in at 4.89. The reason this is interesting, is because older literature suggests the normal range ends at 5.0. There are calls to make the normal range end as low as 3.0, because there is some evidence that this is a precursor to serious disease. And what is serious? Well, technically hypothyroidism starts at 10.0. And if that's the case, what am I dealing with then? Below 10 but above 4.5 is what they call subclinical hypothyroidism. It seems there's a lot of controversy about the TSH level at which to intervene, but age is a factor. We just won't know if it helps me until I start the drugs and do labs again in six weeks, though I may feel something quickly. I also learned that iodine mostly drives your thyroid, and there's little question I don't get very much.

At the end of the day, I'm only a little out of normal range, but again, the difficulty of getting my cholesterol and weight in check suggests this could be a contributing factor. I think the thing that really brought it home though was the idea that maybe I'm not just mentally tired, I'm actually tired because I'm not producing hormones at the right level to regulate all my shit. I think it's pretty cool that my doctor picked up on that.

This is all difficult for me to roll with I guess because it's wholly unsettling to learn that some essential part of my body isn't working entirely as intended. And I have to get a colonoscopy too, because I'm at the age where I need to do that. God only knows what that's gonna look like with my history of lower GI nonsense. I'm having what I would consider an increasingly solid year for mental health, understanding myself, getting comfortable with who I am maybe for the first time in my life, and it seems unfair that my body isn't willing to celebrate accordingly.

Blessings, karma, luck, probabilities

posted by Jeff | Wednesday, August 11, 2021, 7:36 PM | comments: 0I had some really good news today, on top of some other good news earlier in the year, and in aggregate, it just seems like there's a pile of good things piling up. One might consider it a blessing or something.

If it's me, it's definitely "or something."

The year has not been without it's challenges and bad news, but none of it was permanently bad. It's funny though how the brain starts working against you, as if to suggest, "Hey man, all that good will come at a price." So you start to wonder, is that next tropical storm going to be a destructive hurricane? Will you get into a car accident? What do you think they'll find in that colonoscopy? I often wonder if our brains are wired to cause this kind of suffering as a survival tactic.

Logically, bad things don't happen as a result of good things. Humans have invented the concepts of luck or karma because it's the easiest way to account for chaos and randomness. Some people like to say that everything happens for a reason, which totally grates on me. It implies there's some mystical plan or force you can't explain. But the reality is that you can explain most everything, even if the underlying reasons are dissatisfying or uncomfortable.

After the last year, I think I said more than once that the only way to roll with things is to embrace chaos. Accept that you can't control all of the things. While I still believe that, I also feel like the best course of action to deal with chaos is to influence probability. I mean, that should be obvious coming out of a pandemic. You could do things to reduce the risk of getting sick, and vaccination reduces the probability to the realm of very unlikely.

Changing the probability is powerful. Your success at work is more probable if you surround yourself with the best people. Your probability of living longer is influenced by what you eat and how you exercise. It's more probable that you'll meet a great partner if you meet more people. You're unlikely to experience an earthquake if you live in Florida. There is randomness and chaos in all of the above, but you can influence the probability.

That good news I was talking about, there was certainly some uncertainty and randomness about it, but there were a series of things I did that made it more probable. I accept that luck was involved, but I also acknowledge that I did something to influence it.

I'll stick with my "embrace chaos" mantra, but add "influence the probability" to it.

We need things to end

posted by Jeff | Monday, August 9, 2021, 6:49 PM | comments: 0One of the things I love about my therapist is that she's good at spotting patterns that I'm oblivious to. We were talking today about the things that seem to be aggravating my anxiety, and she observe that they all have non-specific endings, and that might be wearing on me.

I've often said that it's nice to have something to look forward to, and that I get anxious when I don't have a trip or special occasion on the calendar. It's not that this comes at the expense of the moment, it's just nice to anticipate fun things. What I never considered was that having some specificity about when difficult things end can also reduce anxiety.

My biggest struggle is the parenting, because ordinarily we would be at the stage where things would be getting easier, and we could be a little less hands-on. But ASD and the delay in emotional development that comes with it means we aren't there yet. In fact, every milestone has come later than expected, and that's rough after 11 years. We don't know when we'll have a child that's more self-sufficient, and love doesn't make that any easier.

I've had a project at work that has taken a lot longer than expected, and it has been hard to nail down when it's going to end. Despite a half-dozen other things landing as expected, the uncertainty of this one has caused anxiety for a long time.

And you know, you may have heard that there's a pandemic, and we certainly don't have a "done by" date for that. At best, we can hope for vaccination availability for kids in the next few months.

There's only so much you can do about certain things, getting them to an end state. But as is the case with anything around mental health, understanding what makes you tick, or interferes with how you roll, helps you out.

The weird Tokyo Olympics

posted by Jeff | Sunday, August 8, 2021, 5:46 PM | comments: 0I've always been a huge fan of the summer Olympics. It's strange to think that, even at my age, there have only been 12 games in my lifetime, so they are kind of rare. I became particularly interested starting in 1992, with the Barcelona games. In college at the time, and deeply fascinated with television production, I was just amazed at NBC's coverage and its storytelling around Spain. To this day Barcelona is a city that I want to visit. The other thing was my growing love for volleyball, and you just didn't get to see the indoor game on TV much in those days (beach volleyball wasn't added as a sport until 1996).

A part of me wanted to figure out how to work the 1996 games in Atlanta, but regrettably, I never let it go much beyond a few random thoughts. By that time, I had more volleyball experience, playing club in college, and I started my coaching career a year after that. But I just loved the idea that sports could bring people together from all over the world, and we could learn about each other's culture in the process, all through television.

Then 2020 came along, and with the pandemic, the games were reasonably postponed by a year. As global vaccination roll out has been glacial, and inconsistent where it has been available, the games were at risk for further delay or cancellation. Finally, it was decided the games would happen, but with no spectators. The first few contests I watched, I think gymnastics and swimming, it was completely strange to see empty arenas. It was even more weird when we got to basketball, volleyball and the gigantic track and field stadium. It felt like you were watching a scrimmage. Then, in the ultimate weirdness, NBC would cut in shots of crappy Zoom video from the homes of the athletes back in the US.

Blatantly missing from the coverage was the usual series of reels about the host country and city. Tokyo is undoubtedly a beautiful place, as you can see from any movie where it has been featured (I adore Lost In Translation). We saw none of it outside of the event venues. Japan is having its worst Covid wave yet, and unsurprisingly, they've insisted that the Olympics be a bubble with people coming from all over. The lack of features about the people and city of Tokyo is such a loss. You can't buy that kind of tourism advertising, and while they obviously can't host tourists right now, it would have been good for Japan long-term.

The depth and quality of the athlete profiles hasn't been great either, even for the US athletes. I know it sounds a little ridiculous, but I value all of that more than the sports themselves in some cases.

Something awesome did come out of this one though, in that the USA volleyball women won their first gold. Despite my general frustration with streaming availability, I did get to see all of their matches, and what a great team. Coach Karch Kiraly is pretty much the most important figure in all of American volleyball, and what a great way for him to check another box after decades of indoor and beach player experience. He built a team, not a collection of superstars, and they earned that gold.

We only have to wait three years for the games in Paris. Hopefully things will resemble something more normal then.

Covid rage

posted by Jeff | Sunday, August 8, 2021, 5:02 PM | comments: 0Things sure got weird again in the last few weeks, as Covid has made a serious comeback. In fact, in places like Florida, it has never been worse. Here in Orange County, we're producing more cases than any time in the pandemic, and our hospitals have never been this full. Understandably, those of us who did the work and got vaccinated as soon as we could, are kind of pissed. It's even more discouraging if you have kids under 12, as the vaccines haven't been cleared for those age groups. As indoor mask mandates return in places, it's not that the vaccinated are particularly at risk themselves, but they may play the role of transmission vector, causing the unvaccinated to get sick. A little rage seems pretty reasonable for a situation that was completely preventable.

I have tried to look at the situation as objectively as possible, and it's hard not to focus on the usual band of white nationalists and anti-science dipshits that suck a disproportionate amount of air out of the room (and replace it with Covid-rich CO2, apparently). You know the people, those who think that everything is a conspiracy, the existence of snow negates climate change, the brown people are at fault for everything and your freedom is conceptually at odds with being a good citizen. That they would be against vaccination isn't that surprising, because aside from being big babies about getting a shot, they're skeptical because government organized the vaccination effort, and government is bad. They lean on the Reaganesque distrust while ironically demanding that only they are qualified to lead the thing you shouldn't trust.

This is why it can be so infuriating, because if you think government is useless (unless it involves military spending, of course), you should be surprised that this was a huge obvious thing that it got right, in a big way. Every human 12 and over in this country is eligible to dodge this horrible disease and reduce its transmission to a rounding error if everyone does it. Mind you, the initial federal plan was to let the states figure it out, but distribution improved pretty quickly in the spring.

Digging into the numbers, these conspiracy driven freaks are of course not a majority of those not vaccinated, though they certainly make it worse by spreading misinformation. There have been countless articles calling out the youth who think they're invincible, the mansplainers who are really just scared to get a shot, and those generally categorized as willfully ignorant about science. But a large number are also people in parts of systems that were already failing them.

Mistrust of the healthcare system itself is a huge problem. Several studies note that the uninsured, insured by crappy benefits or otherwise previously screwed by the insurance/healthcare system are among the most likely not to be vaccinated. Many are worried about the possible day of minor symptoms that often come with the shot, because they can't take off work and risk being fired. Minority communities are naturally skeptical of anything government provided, because the same government can't own up to inequality, or worse, won't correct for it. The truth is that I can't empathize with every reason out there, as a white, hetero male with great health insurance. That doesn't mean the feelings aren't real.

It's the systemic failures that should bother us the most, but I fear we will overlook them with the noisy people yelling at a CPAC gathering. I have said since the start of this pandemic that we desperately need to reform our healthcare system, because access should not be based on insurance, which is in turn based on employment. I can tell you, it even fails when you have the best possible insurance situation. We're fighting now with the insurance company over an MRI that one of Diana's doctors ordered, so he can do an injection that will treat back pain that's preventing her from sleeping normally. A real doctor decided this was necessary, and any world where you have to fight a bureaucracy to get it paid for is broken. I don't understand why anyone wants to keep this system.

The rage over where we are is justified. I do worry that its target is the sideshow instead of the real underlying problems.

Appreciation for my partner

posted by Jeff | Friday, August 6, 2021, 11:54 PM | comments: 0Diana and I were talking last night about some of the stress and absurdity of the last year, and while reading about the stress that the pandemic has imposed on relationships, I am happy to report that our relationship was never strained by it. In fact, if I had to limit social interaction and generally be stuck, I can't imagine a better person to be stuck with.

A lot of people frequently refer to marriage as requiring "work" and other such commitments. While I don't consider that invalid or a fault, I can say that it is not characteristic of our relationship. For all of the stress we've endured in the last 18 months, very little of it has been interpersonal. It is relatively rare that we have conflicts about anything serious. Our trust for each other is implicit, but strong.

If you were to ask me why it seems so easy, I'm not sure I could pin it down, exactly. At the very least, our interactions are rarely contentious. The hardest thing we share as a couple is parenting, and in that area, we generally give each other a ton of room, and tap out unconditionally when we feel spent and can't roll. Even the joke about loading the dishwasher wrong is so ancient history that it's not a thing.

We do have some common interests, but I would say that we arrived at that with some refinement. She came around to theme parks pretty fast, and I came around to theater more as someone who always had the interest, but not the professional "in" to really appreciate it. We also have our own things, like me and video, and Diana's quilting.

At the end of the day, when we say goodnight, I get the feels that I had when we first met. I guess that's surprising because after 14-ish years, there isn't a lot of novelty. That's something that I never thought about in my horny college years, about what happens when very little is new. I think we're both in a place where midlife is a time for discovery and doubling down on what it means to be our authentic, true selves, instead of being stagnant. Every single day we get better because we're willing to keep learning, and I love that about us.

Enjoy this hot and sweaty photo of us on the first date night we've had in a few months. At Epcot Food & Wine, because we live here.

The surprising feeling of good feelings

posted by Jeff | Sunday, August 1, 2021, 7:40 PM | comments: 0One of the things my darling offspring reminds me about is the feeling of extraordinary joy and excitement that we don't feel in quite the same way as adults. I'm happy to report that I have in fact felt that a number of times recently, and it's surprising.

It's not that I haven't experienced joy in the last few years (though if that was the case, it doesn't mean something is wrong with me), it just hasn't been to the extent that I would consider "childlike" in nature. There really is something different about it. When I was a kid, I remember trying to describe it to my mom as a "tingly feeling in my butt," which she did not understand. As an adult, I would say that the physical manifestation of this kind of anticipation and joy is a good anxious feeling that you feel all over, but for me, especially in my hands and feet, and yes, maybe in my lower abdomen. It's paired with a dominant cycle of obsession in the brain, which sometimes makes it harder to sleep.

I've always felt like I needed something to look forward to, but I don't think that comes at the expense of living in the moment. The excitement and joy about things coming soon generally translates into more joy in the moment. What has felt particularly good lately is that the scope of joyous things has been pretty wide. I can recall a short trip recently that felt amazing, but also lying down for a nap yesterday. I was a little too excited about the nap though, so it didn't result in much sleeping.

Where were these feelings before? Sure, I can blame some of it on the pandemic, but I'm coming to understand some other factors as well. A small part of it might just be adulthood, but it's not a huge factor. Many of the serious factors are in the past now, but combined with a greater focus on letting things roll off, and maybe just coming to grips with the ephemeral condition of life, things small and large excite me with the wonder of a child. My curiosity is strong about many things.

I'm not going to lie, it helps that a lot of good things have happened this year. Some very important things happened that fundamentally change the trajectory of our lives. Some were by design, some were purely by accident. I mean, it's not all fun, like I have to get a colonoscopy because the age to start screening changed, but it's mostly more fun.

The last month or two, I've felt that we were on the edge of a change in how things were going. It's hard to describe. I just know that I want to keep moving toward it.